Summarizing and Paraphrasing in APA Style

- Written by Lucas Street

- Published on 01/07/2026

Writing in APA style usually involves using sources as evidence, but writers who are accustomed to relying on quotations in their essays may stumble when trying to adhere to APA guidelines. According to The APA Publication Manual, 7th edition:

Published authors paraphrase their sources most of the time, rather than directly quoting the sources; student authors should emulate this practice by paraphrasing more than directly quoting. (American Psychological Association, 2020, p. 269)

So, APA prefers that writers minimize their use of quotations–but how, exactly?

Paraphrasing and Summarizing

These two terms are often used interchangeably, but they’re actually quite different. A summary conveys only the main point of a text, all in your own words. Summaries are short–just a fraction of the original text’s length.

A paraphrase, on the other hand, “restates” one particular passage “in your own language” (APA, 2020, p. 269). The paraphrase may end up shorter than the original text, or it could be about the same length.

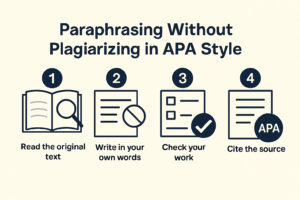

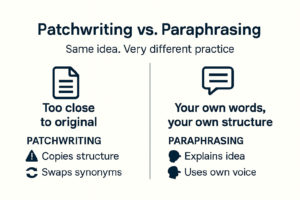

In both cases, the summary or paraphrase must accurately represent the text without using any of the original language. This is to show that you understand what you’ve read: it takes more mental energy and effort to come up with your own way of saying things, whereas changing only a few words… doesn’t. (The latter is often called “patchwriting,” i.e., a failed paraphrase–or, more charitably, a step along the way to a proper paraphrase.)

It’s hard to restate a complex idea in fresh language all in one go, which is why most of us dump some of that cognitive load one step at a time: first, changing some of the complex terms to more accessible synonyms, then going back over the text until we truly understand it, and finally putting the idea all in our own words.

The problem comes when we stop at that first step (inserting synonyms) rather than completing the task of putting an idea into all our own words. Failure to do so can be considered plagiarism, but at the very least it suggests that the writer didn’t fully understand the passage they were trying to paraphrase.

Some Examples

Let’s take as an example a 2024 article by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), titled “AI has an environmental problem. Here’s what the world can do about that.” A summary of this article would convey the main idea of the entire piece, like so:

UNEP (2024) enumerates the many ways increased AI use is significantly harming the planet but also mentions a few initiatives where AI could–if used responsibly–actually help humans address the climate crisis.

This summary doesn’t get into the weeds of particular pros or cons to AI; instead, it gives the reader a sense of the piece’s overall argument so they can choose whether to read it for themselves.

If you wanted to highlight a specific passage from the article, you would use paraphrase rather than summary. Here’s an example of how to do so without inadvertently inviting accusations of plagiarism. First, the original passage:

The proliferating data centres that house AI servers produce electronic waste. They are large consumers of water, which is becoming scarce in many places. They rely on critical minerals and rare elements, which are often mined unsustainably. And they use massive amounts of electricity, spurring the emission of planet-warming greenhouse gases (UNEP, 2024).

If you wanted to highlight this particular pitfall of AI, you could do so by paraphrasing it like this:

Rampant AI use, via the ever-expanding data centres that enable it, poses a grave threat to our planet’s health (UNEP, 2024).

Notice how this version summarizes the idea behind the words, without using any of UNEP’s language or original sentence structure.

|

Read actively. Whether you’re attempting to summarize or paraphrase, help yourself out by first annotating (jotting notes in the margins of) the original piece. Look up words you can’t define on your own, and write down the definitions you find. Put the text away once you think you understand it. Jot down the main idea of the entire piece (if summarizing) or the particular passage (if paraphrasing). This will keep you from focusing too much on the original language. Double-check your draft: Once you’ve written an initial summary/paraphrase, only then should you look back at the original text to ensure you didn’t use any of its language. If you find a word or two that’s the same as the original, enclose it/them in quotation marks. Always cite! No matter whether you’re quoting, summarizing, or paraphrasing, you always need to include an in-text citation. Remember, quotation marks show that you’re borrowing someone else’s language. The citation shows that you’re borrowing an idea. Final thoughts: Whether you’re summarizing or paraphrasing, the goal is the same: to explain the idea behind a passage in fresh language. Only then do you both avoid inadvertent plagiarism and show that you’ve actually understood the text you’re writing about. |

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

United Nations Environment Programme. (2024, September 21). AI has an environmental problem. Here’s what the world can do about that. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/ai-has-environmental-problem-heres-what-world-can-do-about

GIVE YOUR CITATIONS A BOOST TODAY

Start your TypeCite Boost 3 day free trial today. Then just $4.99 per month to save your citations, organize in projects, and much more.

SIGN UP