Paraphrasing Without Plagiarizing in MLA

- Written by Lucas Street

- Published on 12/02/2025

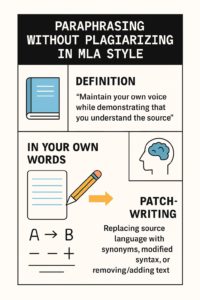

Many college students have a serious misconception about paraphrasing that can actually lead to inadvertent plagiarism. To get on the same page and clarify this misconception, let’s take a look at the definition of paraphrasing according to The MLA Handbook, 9th edition:

Paraphrasing allows you to maintain your voice while demonstrating that you understand the source because you can restate its points in your own words and with your own sentence structure. (Modern Language Association 98)

In other words, paraphrasing involves taking a passage and writing the gist of its meaning “in your own words.” Contrary to common belief, paraphrasing is not taking a quotation and modifying it by swapping out synonyms. That’s something else entirely: “patchwriting,” a term Rebecca Moore Howard coined in 1993. Most institutions of higher learning view patchwriting negatively, sometimes even seeing it as a form of plagiarism.

What Is “Patchwriting”?

According to Howard, et al.:

Patchwriting [is] reproducing source language with some words deleted or added, some grammatical structures altered, or some synonyms used. (181)

So, for example, a patchwritten version of the above definition might look like this:

Howard defines patchwriting as replacing parts of the source’s language with synonyms or changing the syntax.

See how similar that sounds to the original? Sure, the author substituted

- “replacing” for “reproducing,”

- “parts” for “some,”

- “the source’s language” for “source language,” and

- “changing the syntax” for “some grammatical structures altered.”

But for all intents and purposes, the patchwritten version is the same as the original quotation. It even proceeds mostly in the same order, with only the “synonyms” idea being moved from the very end to closer to the middle.

Many college professors would give that so-called “paraphrase” an F, or even a zero for plagiarism. Obviously, we don’t want that! But even more importantly, patchwriting doesn’t give the reader confidence that the patchwriter truly understood the passage they’re trying to paraphrase.

Another Example

Plugging in synonyms is the most common way patchwriting manifests, but it’s not the only way. can. Let’s look at another example–this time, the opening sentence from one of the most famous English novels ever written:

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. (Austen 5)

Here’s a patchwritten version of the above:

Jane Austen claims that this is a fact everyone at the time believed: a bachelor who has a lot of money needs only a spouse to complete him.

Why is this patchwriting? Not a single word is copied from the original, after all. True–every word is different. But the patchwritten version closely follows the order and syntax of the original passage, substituting every word with a synonym and stitching (or “patching”) it all together with some connective tissue of the writer’s own. It doesn’t matter that no exact language is copied; the sentence construction itself is.

Plugging synonyms into the same sentence structure can put a writer just as much at risk of plagiarism as using exact language without showing it’s being quoted. And again, it doesn’t show that the writer truly understands what they’ve read.

Paraphrasing Properly

Contrary to what some folks might think, patchwriting isn’t necessarily a sign of laziness, let alone a desire to fool the reader by passing off a source’s words as the writer’s own. Instead, it happens, according to Howard, et al., because the reader has “uncertain comprehension” of a source (182). In other words, it’s a step along the way toward a true paraphrase–but it ain’t there yet.

Here’s an example of a proper paraphrase of the Austen quotation:

With typical droll wit, Austen’s opening sentence skewers the notion that respectable men should seek nothing more than to marry respectable women. (5)

Notice how this version summarizes the idea behind the words, without using any of Austen’s language or original sentence structure.

|

Re-read the original passage, using active reading techniques such as annotation, until you fully understand it. Don’t look at the text while you attempt to paraphrase it. Why? Because when you’re looking at the original, those words and sentence structures get stuck in your head, and it’s really hard to think of any other way to say it. Check your work: Once you’ve drafted your paraphrase, then look back at the original to see if you inadvertently used any of its language. If so, either enclose the word(s) in quotation marks, or rewrite that part so it’s truly in your own words. Don’t forget to cite! Paraphrases still need an in-text citation, even if you don’t use any of the author’s original words. Remember: Paraphrase isn’t about trying to change the way something’s said. Instead, it’s about explaining the main idea behind the passage in all your own words. That’s how you demonstrate that you’ve understood it–which, as the MLA explains above, is what we should be aiming for whenever we write about a text. |

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. Penguin, 2008.

Howard, Rebecca Moore, et al. “Writing From Sources, Writing From Sentences.” Writing & Pedagogy, vol. 2, iss. 2, 2010, pp. 177-192. The Citation Project, www.citationproject.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/HowardServissRodrigue-2010-writing-from-sentences.pdf

Modern Language Association of America. MLA Handbook. 9th ed., Modern Language Association of America, 2021.

GIVE YOUR CITATIONS A BOOST TODAY

Start your TypeCite Boost 3 day free trial today. Then just $4.99 per month to save your citations, organize in projects, and much more.

SIGN UP